Cold comfort

Dunking yourself in icy water is a hot trend. Research shows it has real benefits.

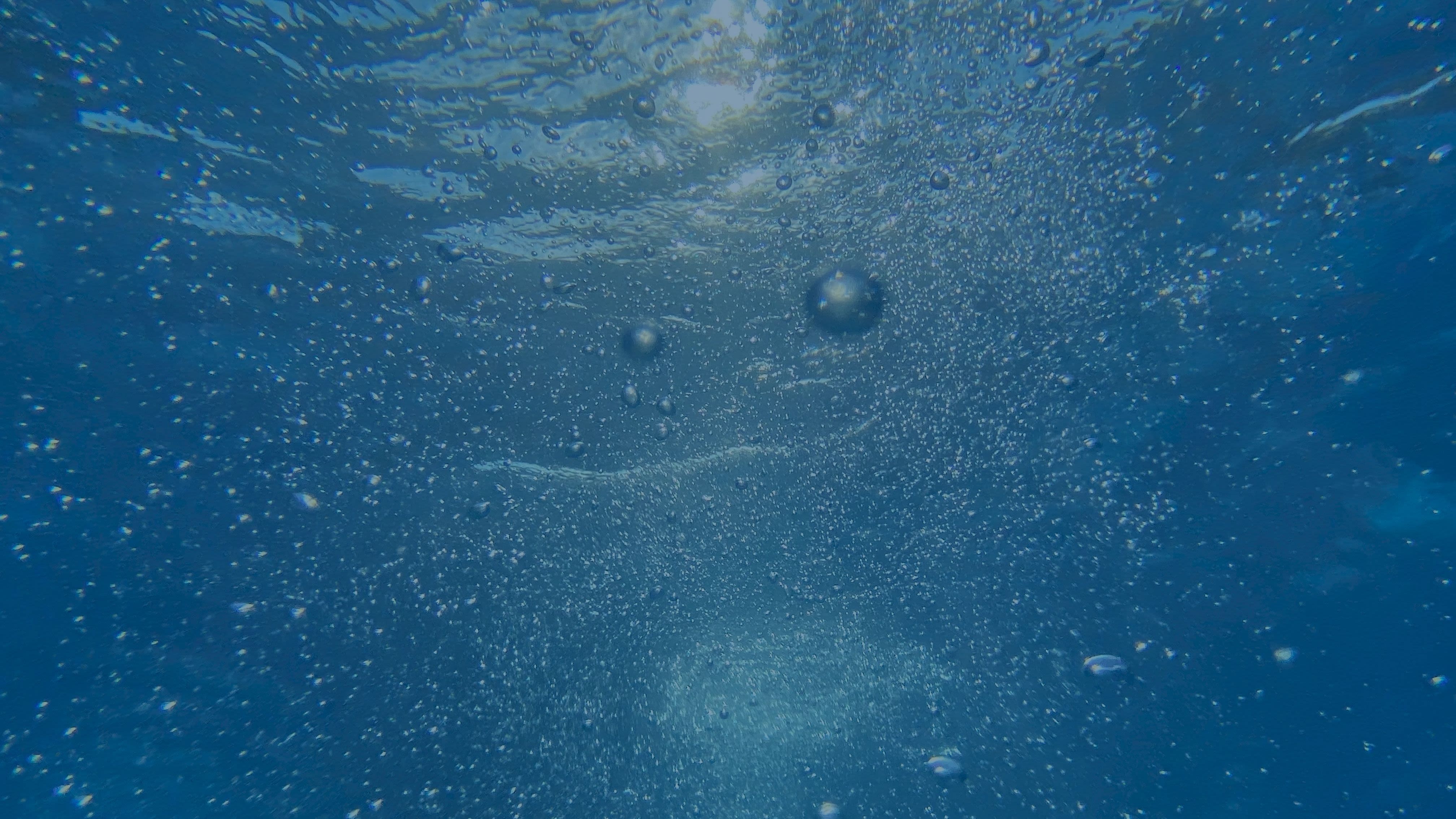

Cold water immersion can improve mood, boost resilience and reduce stress - if you can get past the initial shock.

Amid all the claims by celebrities, sportspeople and influencers about deliberate cold water immersion, there is one undeniable truth:

It is not a pleasant experience.

First-timers gasp, swear, squeal and grit their teeth.

Some even panic.

“It’s quite stressful,” says Kevin Kemp-Smith (pictured), an Assistant Professor at Bond University who still struggles with his own ice bath routine.

The chilling jolt got Dr Kemp-Smith and his colleague Dr Mathew Ono thinking. What drives a healthy person to inflict such discomfort upon themselves? What do they get out of it?

To find out, the pair and their team conducted a scoping review that examined 13 international studies into cold water immersion (CWI). Cold water immersion: Exploring the effects on well-being – scoping review, published in the International Journal of Wellbeing, is believed to be the first to examine CWI’s effect on healthy adults.

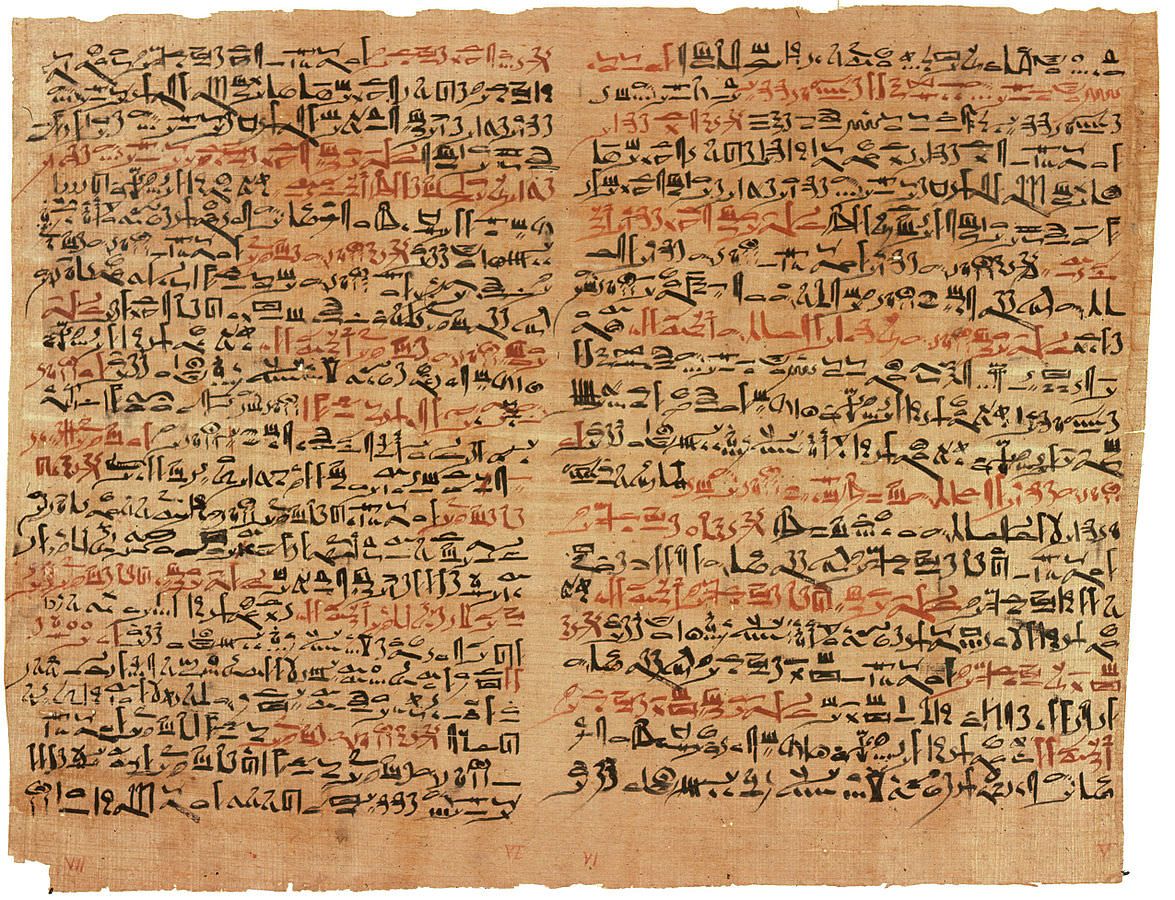

The Edwin Smith Papyrus.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus.

The history of cold therapy

More than just a TikTok fad or fundraising stunt, cold therapy has been used for thousands of years. The Edwin Smith Papyrus, dating to about 1600 BCE (though likely based on material from as early as 3000 BCE), describes a poultice made from crushed fruit, mason’s mortar and water applied to inflamed lesions. This mixture likely functioned as an early form of cryotherapy, leveraging evaporative cooling.

Greek physicians Hippocrates (460–370 BCE) and Galen (129–210 CE) went further. Hippocrates advocated cold water immersion for fever management, while Galen developed a cold cream of olive oil, beeswax and water.

By the 19th century, open-water swimming was recognised for its physical and mental health benefits. In Australia, winter swimming clubs began appearing in the early 1920s with the Bronte Splashers in Sydney, followed by the iconic Bondi Icebergs. Today the Australian Winter Swimming Association has more than 5000 members across 42 clubs who compete weekly from May to September.

Use in sport

Ice baths have become a popular recovery tool among athletes after training and competition. Dr Kemp-Smith says there is a growing evidence base behind the practice.

“The main findings are that ice baths can reduce muscle soreness and the feeling of exertion,” he says. “The other critical element is the release of adrenaline and noradrenaline, the body's fight-or-flight chemicals. These are the brain chemicals that tell you it is not a great idea to immerse yourself in the cold. Overcoming this thought and actually getting into the cold is how people build resilience and determination. Dopamine is another chemical that is released from the brain at the same time and it causes you to be alert and increase your focus and provides a feeling of wellbeing. Following on from that is serotonin, another neurochemical that helps you feel relaxed and calm, and plays a key role in maintaining a healthy mental state. It’s the same process as the runner’s high. It’s addictive.”

Celebrities

Celebrities including Usher, Mark Wahlberg and Harry Styles have praised CWI. Lady Gaga says it is part of her post-performance routine. Philanthropist Melinda French Gates has been practising cold plunges for a decade.

“If you can get through that, you’re like, OK, I can basically do anything today,” she says.

Big wave surfer Laird Hamilton uses CWI to increase his resilience.

What the Bond researchers found

All 13 studies examined by the Bond University team were qualitative in nature, focusing on how people felt, rather than measuring quantitative factors such as heart rate, temperature, and blood pressure.

“I think that’s important,” Dr Kemp-Smith says. “Whereas data can be confusing and can be manipulated, when it's qualitative, I just record what you say and report it verbatim.”

Everyone involved in the studies was practising CWI in outdoor settings such as open lakes and coastal waters in the UK, US, and Europe. The average temperature the participants were exposed to was 13.78C, with the coldest being 4C and the warmest 19.9C. They were participating in CWI 2.5-8.5 days per month, with durations from 5-20 minutes.

The scoping review identified four themes:

Physical and psychological benefits

Many of the studies found CWI can improve mood, reduce stress and have anti-depressant effects. It also helps people become more mindful and aware of their bodies, which can boost overall well-being.

Sense of connectedness

CWI often involves social activities such as group swims which help people feel more connected to others. This can enhance feelings of support and happiness, which are important for mental health.

Personal growth

The discomfort of cold water can help people build resilience and self-regulation skills, contributing to personal growth. This can improve the ability to handle stress and adversity.

Connection with nature

CWI, particularly in natural environments such as lakes or seas, fosters a strong connection with nature which is associated with positive well-being.

CWI Options

At its most basic, trying CWI at home is as simple as some bags of ice dumped in a bathtub. Portable ice tubs are available for less than $100, while more expensive models with filtration and bacteria-killing ozone generators cost thousands of dollars. There’s even a booming online community offering tutorials on how to convert chest freezers into DIY ice baths.

The cheapest way to experience CWI is in nature. That can be challenging on the Gold Coast where the ocean temperature drops to about 21C in winter, which is more accurately described as barely-cool water immersion. In contrast, waters off Sydney get down to 16.9C, while Melbourne reaches 11C. Hobart is the natural environment for cold water swimmers year-round, with ocean temperatures ranging from 9-17C.

The convert

Dr Kemp-Smith says he and his wife are now ice bath devotees, using a cheap inflatable ice bath and a commercial ice machine.

“We use the pool in winter when it drops down to about 12C but the rest of the year we use ice,” he says.

But even with practice he’s still not used to entering 12C water – the temperature of the ocean surrounding the Falkland Islands.

How cold is cold enough?

The 13 studies examined by the Bond researchers spanned ice bath temperatures from 4-19C, with an average of 13.78C.

“Everyone’s tolerance is going to be different,” Dr Kemp-Smith says. “You might go, ‘Oh man, this is really cold. I don't think I can get myself in. But if I take a few breaths and focus, maybe I can stay in’. You’re looking for a temperature that is tolerable and safe. Some studies have shown slightly warmer temperatures around 15-16C with a longer duration up to an hour have the same effects as a colder temperature, say 4C for a shorter 1-4 minute immersion. There are no hard or fast rules; it is what the individual can safely undertake."

Risks

Anyone planning to try CWI for the first time should talk to their doctor first, with risks ranging from bacterial infection from dirty water to heart attack. Royal Life Saving Australia released a position statement on CWI last year, saying that “as with any aquatic activity there is an inherent risk of drowning”.

The shock of entering cold water can cause hyperventilation, increased heart rate and blood pressure and loss of breathing control. It’s also important not to overdo it, as hypothermia can set in during extended exposure to cold water. People with very low body fat are particularly susceptible to hypothermia.

“It is important that you consult a registered medical doctor first to see if you have any underlying health conditions that could be worsened by deliberate cold exposure,” Dr Kemp-Smith says. “You might have Raynaud’s syndrome, which causes reduced blood flow to the extremities. Pregnant women need to be cautious, and some people may experience a panic attack if they get in too quickly. Oftentimes if someone is competing with friends or colleagues, or they're competing online, they can go too extreme, too quickly.”

Younger children should also avoid CWI, Dr Kemp-Smith says.

“They don’t have an effective shivering response and find it difficult to control their body temperature as effectively as adults.”

Beginner tips

Dr Kemp-Smith says CWI newbies should undertake no more than 2-3 sessions of 1-5 minutes per week, totalling no more than 10-15 minutes at temperatures they can tolerate. Starting with cold showers can be a good way of easing into it, he says. For those seeking a cold water hit in nature, beware of environmental hazards such as currents, waves and wind. It is a good idea to buddy up with another cold-water diehard, particularly if you’re dipping in nature.

Future research

With the scoping review complete, Dr Kemp-Smith says he is interested in researching the benefits of full body immersion in cold water versus cold showers.

“Not everyone can afford an ice bath, but it's very easy to just turn down the hot water in the shower,” he says. “How cold should the shower be to get a benefit? How long should I stay under the shower for? I’m also interested in the physiological changes in the body.”

Exposure to cold converts energy-storing white fat into beige or brown fat, which burns more calories than white fat to generate heat through a process called thermogenesis. This calorie-burning effect improves metabolism, helps regulate blood sugar, and may protect against obesity and diabetes.

Dr Kemp-Smith is also curious about CWI’s impact on inflammatory markers in the blood, and whether it might be a treatment for people with arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. The search for cold comfort continues.

Published on Wednesday, 23 April, 2025.

Original thinking direct to your inbox

Stories from Bond